Eighty years before Vasco da Gama reached India and kickstarted the Age of Exploration, another great seafarer, admiral Zheng He, commanded a grand navy to spread the influence and prestige of Ming China. Under his leadership, the Chinese fleet embarked on seven voyages to establish and facilitate peaceful diplomatic and trade relationships with foreign countries, sailing from Southeast Asia to India, and from the Persian Gulf to East Africa. The so-called “Treasure Fleet” was a sight to behold, numbering over 300 vessels.

Besides the giant “treasure ships,” over 120 meters long, the armada consisted of many supply vessels, warships, water tankers, and patrol boats, carrying over 28,000 men. The Treasure Fleet fulfilled its mission, increasing the prestige of China and its emperor overseas, but it failed to take the next logical step. Following Zheng He’s death, the voyages abruptly ceased. The fleet was dismantled, and China closed its borders to the world, leaving supremacy over the high seas to the emerging European colonial powers.

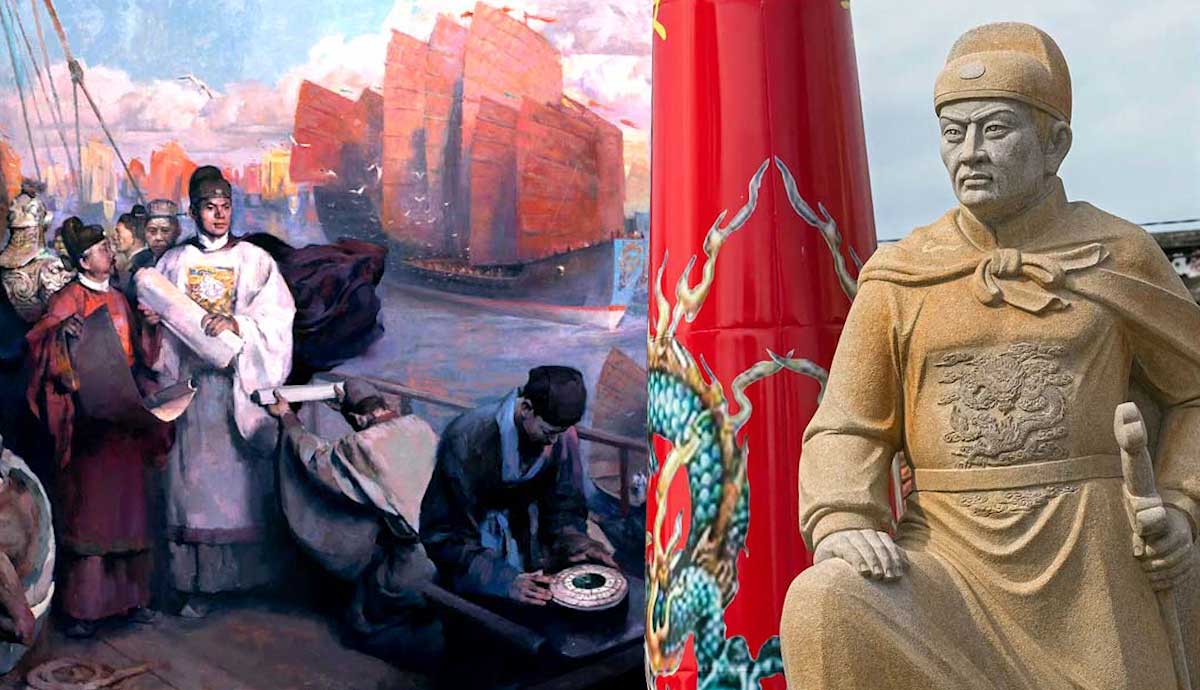

Zheng He, an Unlikely Admiral

Considering Zheng He’s background, it is odd that he became one of the greatest admirals and seafarers in the history of China and the world. Born in 1371 CE to a prominent Muslim family, Zheng He, initially known as Ma He, spent his childhood in the landlocked Yunnan province controlled by the last remnants of the Mongol Yuan dynasty.

The future admiral would probably never have seen the sea if fate did not intervene. When he was ten years old, Chinese forces invaded the region and overthrew the Mongols. His father perished in the fighting, and Ma He was taken as a prisoner. A disaster to some, for Ma He, this was an opportunity, the beginning of a truly remarkable journey that would take him far from home and far from China to places that existed only in a young boy’s imagination.

After a ritual castration (a common practice at the time) Ma He entered the Ming court as a eunuch. Here he caught the eye of Zhu Di, one of the emperor’s sons, who took him into his service. Over the next decade, Ma He would distinguish himself and rise to become one of the young prince’s most trusted advisers. When Zhu Di rebelled against his late father’s successor, Ma He joined the cause, leading the prince’s forces at the battle of Zhenglunba (near Beijing).

Skilled in the art of war and strategy, he defeated the imperial troops and claimed the throne for his friend. Zhu Di did not forget this, and after becoming “the Yongle Emperor” in 1402, Ma He was renamed Zheng He in honor of this battle. He also became the second most powerful man in China, the emperor’s trusted confidante, and an ideal choice for the grand plan to bring the Empire back to the world’s stage.

A Match Made in Heaven

Zhu Di’s father founded and consolidated the Ming dynasty, fighting brutal battles against the Mongols. Now, after both external and internal circumstances had stabilized, the Yongle emperor could begin preparations for his grand plan: to demonstrate Ming power to the world and to revive the golden eras of the Han and Tang dynasties. Instead of using force, the new emperor wanted to increase China’s influence and prestige through soft power and diplomacy. This ambitious plan required an intelligent and capable leader who could be the emperor’s trustworthy ambassador in far-flung lands. Unsurprisingly, the choice was simple — Zhu Di’s close friend and associate, Zheng He.

The plan involved using a large navy, which would sail to distant lands to “convince” foreign rulers to recognize China as their superior and its emperor as lord of “all under Heaven”. In return for gifts of tribute, China would establish and maintain trade and diplomatic connections. By that time, China was already a naval power. Both the Song and Yuan dynasties had kept large navies and controlled the South China Sea. Under Kublai Khan, the Mongols had built a fearsome naval force consisting of thousands of ships and deployed it during the failed invasion of Japan. Thus, the Ming inherited a formidable navy. But the emperor’s plan was more ambitious. The existing ships would serve as the core for a more impressive and massive grand fleet commanded by Zheng He.

The Largest Fleet the World Has Ever Seen

To realize his grand plan, the emperor put all the resources of his vast Empire at Zheng He’s disposal. All the shipyards along China’s coast had one job — to build a great fleet. Under Zheng’s oversight, workers cut down trees, processed lumber, and created new shipyards to fulfill this mammoth task.

Scores of new vessels were built, but the highlight of the fleet was undoubtedly the famed “treasure ships” or baochuan. These vessels were giants in every sense of the word, 122-meter-long (over five times the size of Columbus’ caravels), hosting nine huge masts, a crew of up to 300 sailors, 60 cabins, and four decks filled with soldiers, merchants, diplomats, doctors, cartographers, and other officials. Historians still debate their exact size, but a recent discovery of an 11-meter-long rudder suggests that the ships may have been as large as claimed.

Besides their mind-boggling size, the ships also used an innovative design. The “treasure ships” and the support vessels — five-masted warships, six-masted troop transports, and six-to-seven-masted transports carrying grain, horses, and water — featured divided hulls with several watertight compartments. Advanced engineering allowed Zheng He to take unprecedented amounts of drinking water on long voyages while also adding much-needed ballast, balance, and stability, essential for smooth sailing over the open seas.

The Treasure Fleet was designed to “show the flag,” to both impress and cow regional rulers. For this reason, the vessels were elaborately decorated, the rigging decorated with yellow flags, sails dyed red with henna, hulls painted with huge elaborate birds, and large eyes painted on the bow. One could only imagine the impression Zheng He’s 300-vessel-armada would leave upon arriving in a foreign port. Indeed, the very sight of the majestic fleet fulfilled its primary aim, to display the glory and might of Ming China and its emperor.

It was also gunboat diplomacy at its finest. Although the Treasure Fleet’s chief purpose was diplomacy, Zheng He’s enormous ships were heavily armed, their huge decks brimming with cannons, one of the greatest Chinese inventions.

The Voyages

The first of seven voyages began in July 1405. Zheng He’s fleet comprised around 255 vessels, 62 of them being enormous “treasure ships” and carrying nearly 28, 000 men. Their first stop was Vietnam, recently conquered by the Ming. After resting in Malacca, waiting for the winter monsoon to sail west across the Indian Ocean, the fleet visited Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) and Calicut on the southwestern coast of India.

The Malabar coast, the center of Indian Ocean trade, was also the terminus of the first three expeditions. The fourth expedition reached Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, while the later voyages advanced further west, entering the Red Sea and sailing to the East African coast. Scholars are still debating if the Treasure Flee rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1420 before turning back due to the lack of wind.

At every stop, Zheng He would establish diplomatic and trade relations with the locals, visit royal courts and collect tribute, including spices, frankincense, ivory, precious gems, and even exotic animals. Most famously, the fourth expedition brought back to China a giraffe, described by a contemporary as qilin — a unicorn-like creature whose head rested on a long neck, over five meters long (evidently an exaggeration). The fourth voyage was also the most impressive, consisting of around 300 ships.

Besides the various goods and animals, the fleet brought to China numerous envoys and representatives of various countries for the audience with the emperor. It was also an effective way for Zhu Di to show Ming China’s power and influence without spending vast sums of money and manpower on costly military campaigns. Zheng He, however, did not shrink from violence when he considered it necessary. He ruthlessly suppressed pirates who had long plagued Chinese and Southeast Asian waters and waged mini-wars with the local rulers unwilling to cooperate.

The Last Voyage

After decades of travel and trade, the cost of keeping the floating metropolis was becoming too prohibitive, even for the ambitious Yongle emperor. His influential courtiers’ complaints about these expensive far-flung cruises were compounded by the renewed Mongol threat on the northern border, forcing the emperor to move the capital from Beijing. Constructing and supplying giant ships became a significant burden to the imperial finances. For this reason, Zheng He’s sixth expedition mainly focused on returning foreign envoys to their homelands.

Then, in 1424, Zhu Di died, and the new emperor who replaced him had different priorities. Zheng He lost his position. His main opponents were more conservative Confucian courtiers, and they now had the emperor’s ear. China was gradually shifting its focus inward to the Mongols and the construction and expansion of the Great Wall.

New military expenditures directly competed with the funds required to continue naval expeditions. Zheng He, however, continued to cooperate with the new emperor, playing a role in the completion of a majestic pagoda and surrounding temple, destroyed centuries later during the Taiping rebellion. He performed his task admirably, as in 1431, and the emperor approved the seventh voyage.

Zheng He’s Legacy

Zheng He’s seventh voyage was to be his last. The 62-year-old admiral died on the return journey in 1433. He was buried at sea, and the fleet turned back to China. Soon after, the emperor, supported by Confucian officials, ordered the ships to be burned and outlawed most maritime trade. In what was a purely political move, all official records of the voyages were systematically destroyed. During the following decades, any suggestion of returning to the high seas was firmly rejected, while China closed its doors to the world.

Despite the attempts of his opponents to erase Zheng He and the Treasure Fleet from history, his legacy remained. For instance, Malacca on the Malayan peninsula, which played an essential role in supplying the grand fleet, became a great port and the hub of a trade network that extended across Southeast Asia up to China.

Furthermore, Zheng He’s voyages had a lasting impact on Asia, setting up migration routes and cultural exchanges that reshaped China and the region. After the Empire abandoned virtually all maritime trade, coastal communities took over, with many residents turning to smuggling and piracy. Further, many of Zheng He’s sailors never returned to China, building their homes and storehouses in ports in Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam. Chinese communities have remained in those regions until the present day.

Zheng He and his seven expeditions brought China to the brink of becoming the main power on the high seas. Then, in a cruel twist of fate, the admiral died, and the Ming emperors reversed their policy a few decades before Europe’s explorers embarked on their own voyages, ushering the old continent into the Age of Exploration and colonialism. When China finally emerged from its long isolation, it encountered a much different world, where the ruler of “all under Heaven” was inferior and foreign fleets ruled the high seas.