The Battle of Shiloh was a complex two-day struggle in the early Spring of 1862 on the banks of the Tennessee River near Savannah, Tennessee, in Hardin County. The movements, engagements, first-hand accounts, and secondary source material have been heavily studied since the fighting stopped. In those years, nicknames, such as the Hornet’s Nest, the Peach Orchard, and Grant’s Last Stand at Pittsburg Landing, have come from the battle. Crucial fighting took place in these now infamous locations, resulting in a different battle on the first and second days.

Fort Henry and Donelson: The Lead-Up to Battle

The Civil War in the eastern theater, and primarily the fighting taking place in Virginia, had come to a stalemate in 1862, following several successful Confederate engagements. In the western theater, the early months of 1862 saw one Union victory after another. Confederate commander of all western forces, Albert Sydney Johnston, created a defensive line in northern Tennessee along the border of neutral Kentucky to protect from a Union invasion into the deep south.

From his headquarters in Cairo, Illinois, Ulysses S. Grant devised a plan with Andrew Foote to have his flotilla transport Grant’s troops down the Mississippi to the Tennessee River and take Fort Henry. They would then move over to the Cumberland River and attack Fort Donelson. Fort Henry was easily taken on February 6th, but after Foote’s flotilla retreated from Donelson due to damage from Confederate battery fire, Donelson proved more of a challenge.

Nonetheless, on February 16th, Simon Bolivar Buckner surrendered control of the fort to Grant with “No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender” (Grant, 1885). The fall of these two forts left most of Tennessee in Union hands and required Johnston to retreat deeper into the Confederate heartland allowing Union forces to gain ground.

For Grant, his superior Henry Halleck took credit for planning the river campaign and was promoted to “the command of all Union troops west of the Appalachians.” Grant was ordered to continue down the Tennessee River and to disembark near Savannah, Tennessee. The strategy was to allow Don Carlos Buell enough time to reinforce Grant with 35,000 additional troops of which Halleck would take command of all 75,000 men (about the seating capacity of the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum) and continue south to the city of Corinth, Mississippi and overtake the vital rail junction of the Memphis and Charleston railroad and the Mobile and Ohio.

Confederate Faith Struggles

In late March, Albert Sydney Johnston found himself in Corinth, Mississippi under intense scrutiny from the Confederate press for allowing the fall of Forts Henry and Donelson and for not repelling the Union invasion. A month earlier, “Confederate high command… began scrambling to send reinforcements to the area.” It was soon decided that “all available forces in the west” were to converge on Corinth, Mississippi. Johnston stayed the commander of these men; however, P.G.T Beauregard, the instigator of the firing on Fort Sumter, would become his second in command (Smith, 2010).

Johnston and Beauregard soon decided that rather than wait for a Union assault on Corinth, the best chance for Confederate victory was to attack Northern forces in their current location and catch them off guard. Johnston left Corinth and headed north towards the Union encampment with plans to launch an assault on April 4th. Delay due to heavy rains and impassable terrain led to a two-day delay and by April 5th, “Beauregard was in despair and wanted to call off the attack.”

A council of war was called for the Confederate commanders as fears arose that the slow movement of the army gave away the element of surprise and surely Buell had reinforced Grant by now, making his force much stronger than the Confederates. Johnston, desperate for victory, overruled his commanders and decided the assault would take place at dawn because he would “fight them if they were a million” (Foote, 1958).

Fraley Field: The Battle Begins

Colonel Everett Peabody, a brigade commander within the 6th division under the command of Brigadier General Benjamin Prentiss, sent out a “small squad… of the 25th Missouri under Major James E. Powell” for reconnaissance in the early morning of April 6th. Powell reported back to Peabody he had contacted the enemy pickets and believed “there was a strong force behind them.” Despite not receiving any orders to do so, Peabody sent out “a much stronger patrol around 3:00 a.m.” to investigate deeper than the first. Major Powell moved southwestward and crossed over the “Corinth Road.”

Half of the 25th Missouri entered a thicket, while the right “of the line…neared an open field, that of John C. Fraley’s.” These Missourians met the 3rd Mississippi Infantry, and both regiments exchanged fire around 5:00 AM. The Battle of Shiloh had begun, and behind the 3rd Mississippi was the whole of Johnston’s Army of Mississippi (Woodworth, 2001).

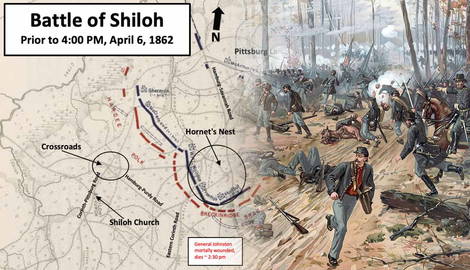

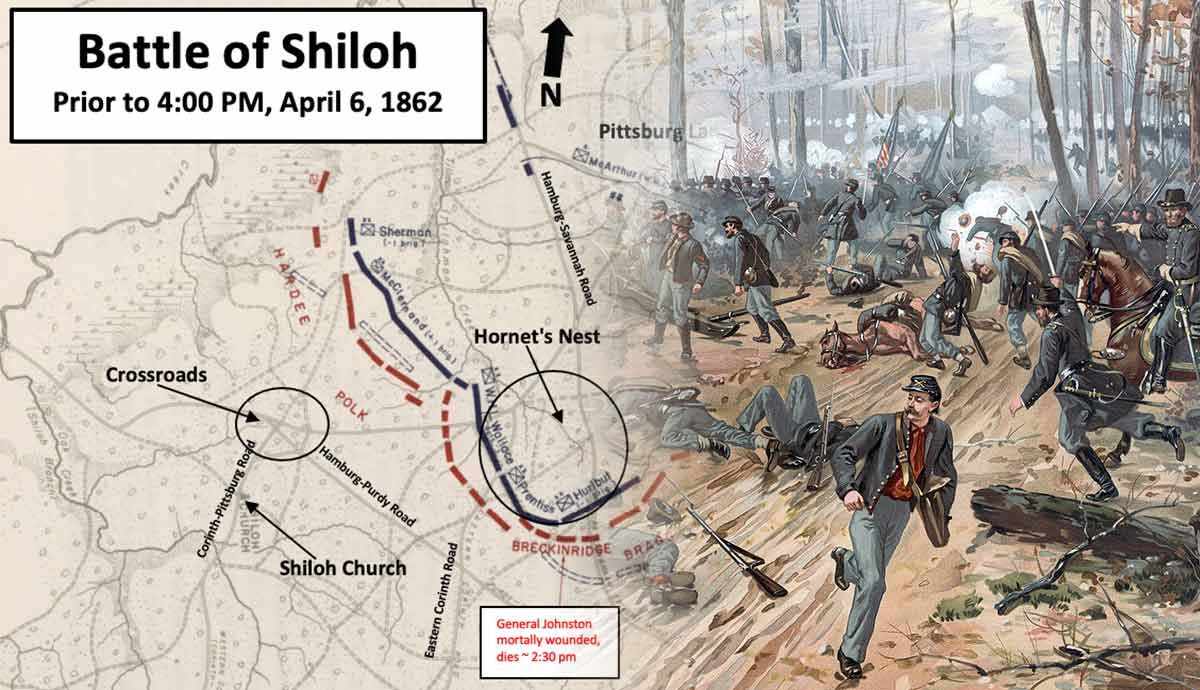

Johnston and Beauregard devised a plan that would only work if it could catch the Federal Army off guard. Hardee and Polk’s Corps would keep Sherman’s and McClernand’s divisions busy while Breckenridge and Bragg would swing around on the bank of the Tennessee River, pushing back Prentiss, Hurlbut, Wallace, and Grant, cutting them off from the river and their base of supplies. Once the Federals combined away from the river, the Confederates pushed them west into Owl and Snake Creek and destroyed them before Buell could reinforce them.

The skirmish in Fraley Field slowed the Confederate advance for roughly two hours and what was set to be a swift movement became a “plodding Confederate advance” when they came upon “the Union camps around 7:00 a.m., they did not find sleeping and surprised Federals… Rather, they found… artillery batteries in line, ready and waiting to meet them” (Foote, 1958).

“My God, We Are Attacked” The Fighting Near Shiloh Church

Reports of the engagement at Fraley Field reached General William Tecumseh Sherman’s headquarters near the Shiloh Methodist church on the right flank of the Federal Army. Sherman’s men were eating breakfast when Patrick Cleburne’s 15th Arkansas of Hardee’s Corps made its way through the fighting at Fraley Field. Rather than wait for the rest of the Corps, Cleburne ordered “Trigg’s artillery to fire on Sherman’s position at 7:30 a.m.” The Federals “jumped up… grabbed their muskets,” as Sherman cried out “My God, we’re attacked” (Sherman, 1875). Sherman’s men repelled one advance after another, never breaking ground for three hours.

To the right of Sherman was Benjamin Prentiss’s camp, from which Colonel Peabody sent out Major Powell into Fraley Field. Prentiss’ unwillingness to relent his notion that there was no significant Confederate assault, led to a slow formation of his division. Even as he was under a full-scale attack, Prentiss refused to believe this was nothing more than a minor skirmishing force. The “third brigade, not yet formed” at the time of the assault presented one of two major gaps in his line of defense. “Half a mile wide” the gap on his left flank proved fatal to his defense of the encampment. Confederate troops broke through this gap and turned towards the west.

Where Sherman had succeeded, Prentiss had failed as his “entire division was retreating” from their camp. Prentiss himself admitted to taking many casualties during the fight that lasted until 11 a.m., one being Colonel Peabody who through his actions saved the Federal army. Following the battle, however, Prentiss would claim to be the savior. It would be nearly a century before Peabody’s actions were recognized by historians and the National Park Service.

“Yes, and I Fear Seriously” The Fighting in the Peach Orchard

To the left of Prentiss was the Division of Stephen A. Hurlbut. Hurlbut began advancing his men from their camp south towards the fighting and “passing through a skirt of woods,” they came upon “a peach orchard… that was in full bloom” at the time. A slew of problems such as brigade command issues plagued Hurlbut in forming his men into a line of battle.

However, the “[biggest] problem was a quarter mile gap that extended from his left on the Hamburg-Savannah Road.” This was soon filled in and Grant, having made it to the battlefield from Cherry Mansion in Savannah, asked Hurlbut “how long he could hold his position,” to which Hurlbut replied “All day.” Hurlbut defended his position in the peach orchard while slowly retreating between 11:00 a.m. and 6:00 p.m., buying Grant the time he needed to set up his line of defense near Pittsburg Landing (Foote, 1958).

The Confederate assault slowed in the peach orchard, a vital location in the wheeling of the Union left flank. Johnston became quite impatient at the lack of momentum by Bragg’s and Breckinridge’s Corps and rode over to the position. In the early afternoon, Johnston was struck by a mini ball from the fighting in the orchard and did not notice any injury. It was not until Johnston’s boot filled with blood that he noticed the seriousness of the injury. The Confederate commander bled out within minutes. Had the wound been discovered earlier, Johnston would likely have survived. A simple tourniquet would have stopped the bleeding (Smith, 2010).

“How I Wanted to Give it to Him Point First” The Hornets’ Nest

Following the death of Johnston, Beaureguard found himself in command of the Army of Mississippi and was eager to continue the assault. By the time Beaureguard took command, the Confederates had “driven back the Union right and left two miles from their starting point.” However, the center of this defensive line, composed of the remaining men of Prentiss’s division and of the division of W.H.L Wallace, had formed a strong defensive position along a lane that would become known as the Hornets’ Nest by many veterans of the battle.

Fighting began at this position around 11:00 a.m. with the Confederates launching their first assault on the Union defensive position along the sunken road. Under direct orders from Grant to “hold the position at all hazards,” Prentiss and his 4,500 men repelled “a dozen separate assaults” by the nearly 18,000 Confederates until “5:30 in the afternoon… an hour before sunset” (Grant, 1885).

Taking the order literally, Prentiss and his division took immense casualties during the fight, and by 5:30 p.m. Confederate forces had encircled the remaining 2,200 men and took them prisoner, including Benjamin Prentiss. W.H.L. Wallace was mortally wounded during the fighting and taken to Cherry Mansion in Savannah where his wife met him that morning to surprise her husband. He would die days later. The fighting at the Hornets’ Nest, while grueling in terms of loss of human life, allowed for Buell’s lead brigade to arrive and support Grant’s defense at Pittsburg Landing

“We May Win the Battle if Not the Day” Grants Last Line

Reinforced by the lead brigade of Buell’s Army of the Ohio, Grant deployed his men on the bank of the Tennessee River near the gunboats Lexington and Tyler; the defensive perimeter was the last line of defense for the Union army. If they were defeated here, they would be pushed into the river and Johnston’s goal of destroying the Army of the Tennessee would come to fruition.

Grant deployed two lines of defense, one paralleled the river and the other ran perpendicular. The right of the line ended at “snake creek” and the left ended at a “deep ravine” with water at a “considerable depth” at the time. This area along the ravine was “its strongest point” and a Confederate blunder occurred when Beauregard sent in brigade after brigade along this ravine in a final effort to wipe the Union army from the battlefield (National Park Service).

The fighting that took place on April 6th, despite strong Union resistance, ended in a Confederate victory. Beauregard, on the night of April 6th, wired Jefferson Davis in Richmond informing him of the death of General Johnston with news of a “complete victory” by the Confederate army. As the night progressed, Beaureguard believed all that would happen the next day would be a mopping up of the previous day’s fighting and no large-scale general engagement would take place (Foote, 1958).

Along the Union lines, however, Grant was preparing for a full-scale counterassault against the Confederate army. The whole of Buell’s army arrived after nightfall. Grant was reinforced with 24,000 fresh troops for the second day. As Sherman and Grant pondered the events of the first day under an oak, Sherman remarked on the brutality of the day with “Yes, lick ‘em tomorrow, though” (Grant, 1885).

The Events of April 7

Beauregard woke on the morning of April 7th to a large-scale general engagement that began at 5 a.m. Lew Wallace had the honor of being the first to engage in combat on the second day. From first light till 10 a.m., the Union army fought out of their defensive positions along the Tennessee River.

After pushing the Confederates away from the river, the second day’s fighting was like the events of the first day, just in reverse. Overwhelmed by nearly 25,000 fresh troops, weary Confederates found themselves continuously driven back south and fighting through the very same locations they had spent the previous day taking from the Union army. At 2:00 p.m. Beauregard was near Sherman’s camp at Shiloh Church not far from Fraley Field, where the battle had begun a day prior. It was from this position that the Louisianian commander began to “wonder about the wisdom of further resistance” (National Park Service).

Soon after, Beauregard decided it best to retreat from the battlefield. After making sure the rear of his army was covered, the Confederates began the march back to Corinth around 6:30 that evening. Grant did not pursue this as his men were “too fatigued from two days’ hard fighting” (Grant, 1885).

The events of Shiloh on April 6th and 7th 1862, although one battle is a tale of two vastly different days. April 6th saw an almost Union collapse. The next day was a revival of the previous day’s events with a different outcome. Although considered an overall Union victory, it is hard to say who won the battle. No ground was gained for either side while both armies amassed 23,746 casualties over the course of the two days. In places like Fraley Field, Shiloh Church, the Hornet’s Nest, and the Peach Orchard, both armies dueled one another only to end up where they began the night before the battle began.

Bibliography

Foote, S. (1958). The Civil War: A narrative. Random House.

Grant, U. S. (1885). Personal memoirs of U.S. Grant. Charles L. Webster & Company.

National Park Service. (n.d.). The Battle of Shiloh (April 6-7, 1862). National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/shil/learn/historyculture/battle-of-shiloh.htm

Sherman, W. T. (1875). Memoirs of General William T. Sherman. D. Appleton & Company.

Smith, J. (2010). The Battle of Shiloh: A Reappraisal. Civil War History, 56(2), 125-148. https://doi.org/10.1353/cwh.0.0099

Woodworth, S. E. (2001). Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862. University of Nebraska Press.