Captain William Judd Fetterman once bragged that he could “ride through the Sioux nation with eighty men.” Assigned to Fort Phil Kearny, near present-day Buffalo, Wyoming, Fetterman led an infantry detachment under the command of Colonel Henry Carrington. Attacks by the Native tribes of the area, particularly the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, who had united under threats from encroaching US settlers and seemingly epidemic Manifest Destiny, had led to a rise in the presence of soldiers and, as a result, confrontations became increasingly common. While the ultimate outcome of the US-Indigenous wars is now clear, the army was not the unmistakable victor at the onset of this era. Fetterman’s boast would be an ominous harbinger, though not in the way he intended.

Fetterman’s Fight for the Land

The land was the essence of the conflicts between the US army and the Indigenous tribes that occupied the plains and the west. Groups such as the Lakota (also referred to as the Sioux), Arapaho, and Cheyenne wanted to continue to live how they had traditionally for generations. These nomadic tribes moved throughout their ancestral and adopted homelands, following the bison herds, which were their main point of supply for food, clothing, and other necessities.

On the other hand, the United States was rapidly expanding in terms of population, with citizens wanting to leave the growing cities and search for wealth in the west. Wagon trains had commenced crossing the country in 1841, and emigrants continued to move across the plains. The transcontinental railroad was under construction, as were dozens of other rail projects that hoped to simplify the travel of people and goods around the United States. Miners were drawn by the siren song of gold hidden in the hills.

With the implementation of these enterprises came changes that disrupted the migration patterns of the bison, polluted waters, and led to dangerous confrontations between the Indigenous and the encroachers. There was simply no way for these two worlds, Native and modern, to live side by side in peace. Native Americans had already been relocated East of the Mississippi, but American settlers found that groups in the west proved harder to subdue.

Protecting Travelers on the Bozeman Trail

Hoping to maintain amity, but first and foremost aiming to protect US citizens, President Ulysses S. Grant sent soldiers to the plains in increasing numbers to build and populate forts. Civil War veterans found a new purpose as “Indian fighters” – a particular area of interest was the area around the Bozeman Trail, which was becoming heavily traveled by settlers. The Trail connected southern Montana, where gold was located, to the iconic Oregon Trail, which hosted over 400,000 settlers.

The Bozeman Trail, named for John Bozeman, who helped improve the trail for passage, passed through parts of Montana and Wyoming, right through the heart of what was once Crow territory. Historically, the Crow, who call themselves the Absarokaa, were friendly both to settlers and the US government, and would even ally with the US army later in the Plains wars. However, in the mid-nineteenth century, parts of this territory were taken over by the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, complicating matters as the Crow were pushed westward.

As the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho increased in number in the area around the Bozeman Trail, the voyage for miners, settlers, and trappers along the Trail became increasingly arduous. Not only did travelers have to deal with challenges like disease (Colorado Tick Fever was common), accidents, and unpredictable weather, attacks by Native forces became increasingly commonplace. The US army responded by building three staffed forts along the route: Fort Phil Kearny, Fort C.F. Smith, and Fort Reno. Fort Phil Kearny lay in what is now northeastern Wyoming, named for a popular Civil War general. It would be the starring location of William Fetterman’s unfortunate decision-making in 1866.

Who Was William Judd Fetterman?

William Fetterman served in the Civil War and chose to remain a regular army member afterward, earning the rank of captain. He was stationed at Fort Phil Kearny beginning in November of 1866, under commanding officer Col. Henry B. Carrington. Carrington had supervised the building of Fort Phil Kearny himself and was known for his talented engineering abilities. However, he was gaining a reputation for showing a lack of aggressiveness in dealing with the indigenous tribes, which hurt his popularity and respect among the men under him.

Fetterman did not hide his disdain for his commander. Though he himself had seen limited action against their enemies, he famously boasted that he could “ride through the Sioux nation with eighty men,” believing the natives to be a weak force just waiting to be cut down.

The soldiers filled their time protecting civilian woodcutters and haymakers who were working for the forts, along with settlers who were staking claims or passing through. They would often be signaled and called out to ward off attacks or break up small skirmishes between these groups and small contingencies of Native warriors or hunters. However, there had not yet been any major, large-scale battles orchestrated against the Indigenous population or vice versa.

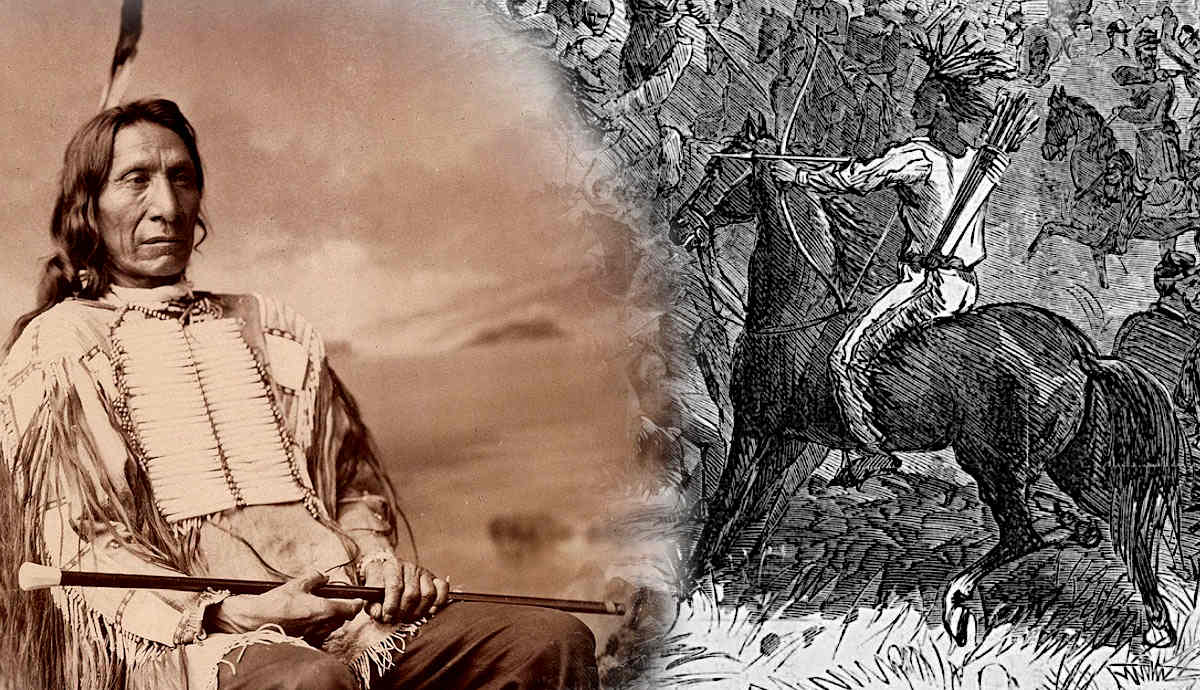

However, what happened to Fetterman’s group on December 21, 1866, would come to be the largest engagement of what was later known as “Red Cloud’s War,” named for an Oglala Lakota war chief who worked to ally the three tribes (Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho) and later negotiate treaties with the US government and army.

On this day, a wood train returning to the fort came under attack from a small band of Native troops. Fetterman gathered a command of exactly 80 men, including another captain, a second lieutenant, members of the 18th infantry and 2nd cavalry, and two scouts. Carrington gave Fetterman and his group strict instructions not to cross over Lodge Trail Ridge. This hill lay a bit beyond the fort, and it was impossible to view what was beyond it until one was practically over it. Fetterman and company confidently rode off and found a group of about ten warriors that had been harassing the woodcutters. This group was led by famed Oglala war leader Crazy Horse, considered by some to be one of the greatest military minds in US history.

Fetterman and his men pursued the group until they reached the top of Lodge Trail Ridge. Here they paused. The native contingency did as well, making themselves easy targets in hopes of encouraging their pursuers to follow. Crazy Horse got off his steed and pretended to check its hoof as if something was wrong with it. Others jeered at the soldiers and shouted insults. Some retellings even indicate that Crazy Horse pulled down his breechclout (all he wore to most battles) and mooned the US army soldiers. Finally, Fetterman could take it no more and ordered his men over the ridge to strike down the offenders. It would be the worst and final decision of his life.

The Hundred in the Hands

Once the group crossed the ridge, they found themselves immediately swallowed by approximately 2,000 Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors. This was not an impromptu strike, but a planned trap orchestrated by the Native force.

Relying heavily on spiritual beliefs to help divine the future of their battle plans, that morning, the war leaders looked to a Lakota winkte, or “two spirited person” to determine the outcome of the day. Winkte, short for winyanktehca, were alternate-gendered individuals, not defined as male or female, often described as living as “half man, half woman.” In the Lakota culture, they were seen as sacred and were relied on for divination and for performing other important cultural duties. The winkte’s name who performed the sacred rituals that morning has been lost to history, but at the conclusion of their visions, they announced to the gathered warriors that they had seen one hundred wasichus – white soldiers – dead in the day’s battle, a victory for the tribes. This vision helped the warriors plan the day’s strategy and their ultimate success.

The entirety of Fetterman’s command was wiped out within twenty minutes. Their bodies were mutilated with the exception of one, and the reasoning behind this was twofold. Firstly, many of the warriors were still feeling the desire to avenge the innocents killed at the Sand Creek Massacre committed two years earlier by US Colonel Chivington and his command. Secondly, some tribes, including the allied groups, believed that an individual went to the afterlife as they lay in death. If a man went to the next world without his eyes, for example, he would wander eternity blind.

The one body that was not mutilated but instead treated with reverence and covered with a buffalo robe was that of Adolph Metzger, a German immigrant who served as a bugler in the army. At the time, buglers were not issued a weapon by the army, so it was unlikely that Metzger had a weapon of any type unless he had saved up money to purchase his own. Instead, he fought with what he had, his bugle, and did so valiantly based on the condition of his instrument when it was later found. It is believed that his gallantry is what led to his body being treated with respect by the victors.

Who Will Take the Blame?

However, respect was in low supply among the remaining army members at Fort Phil Kearny. Someone had to take the blame for what was originally labeled as “Fetterman’s Massacre.” Given his history of reluctance to engage with Native forces, Commander Carrington was an easy target, and the president initially made moves to court martial him. However, instead, he submitted the matter to a court of inquiry, which later exonerated Carrington.

Still, the damage was done, and Carrington was relieved of his command immediately after the disaster, his career in the army in tatters. His wife attempted to return his name to good graces by publishing a book two years later, but he struggled to maintain his reputation until much later in his life, when more details of the event began to come out.

While some still call it a “massacre,” many began referring to it as “Fetterman’s Fight” – a more accurate depiction when one examines the true definition of a massacre and considers the fact that the annihilation took place during wartime conditions. The allied Native contingency would refer to it as the Hundred in the Hands, the crown jewel in a series of three battles that would make up Red Cloud’s War. The war would end with the Fort Laramie Treaty less than two years later, and would go down in history as the only time that any indigenous group was successful in winning concessions from the United States government, though this accomplishment would prove short-lived.